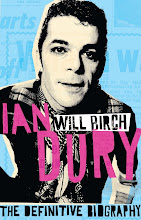

Ian at Kara Lodge (photo courtesy of Jemima Dury)

The summer of 2013 sees the first major exhibition of the

paintings and artworks of Ian Dury.

The exhibition ‘Ian Dury: More Than Fair - paintings, drawingsand artworks 1961-1972’ is being staged at the Royal College of Art,

Kensington Gore, London SW7 2EU from 22 July to 1 September (Closed Mondays). Free

Admission.

The show has been put together by Ian’s daughter Jemima Dury, ‘former confederate’ Kosmo Vinyl, and one time Stiff Records art director

Julian Balme. More than 30 pieces will be on display, most of them coming from

the Dury family archive, with some pieces loaned by Ian’s friends, and

collectors.

The Royal College is an apposite venue for such a

celebration; Ian gradated there on 8 July 1966 with a diploma as an Associate

of the Royal College of Art. He went on to teach art at various schools and

colleges before forming his band Kilburn and the High Roads in 1971.

Lee Marvin

Ian: “When I was a painter I got good enough to know my limitations. To exactly place myself, and ambition is one of the driving forces of anyone’s creative output and the thought that you’re gonna be the best. You want to rank with your heroes like Renoir. There’s a room at Kenwood with a Rembrandt and a Vermeer and a Frans Hals. Once you’ve done twelve years, which I had, you get to point where you know that however hard you try, fifteen hours a day, you reach a point where you realise you ain’t necessarily gonna be good enough to please yourself. Good enough to spend that time agonising over it. Lucien Freud is always grafting, it’s pure frustration. If you’re prepared to put up with that life, you’ve got to believe in yourself to a very huge extent and I’d sooner fall asleep with a book.”

Princess Rockeberty

Ian: “A lot of

us got into The Royal College Of Art.

They called us the Walthamstow Cockneys. A load of us got in - 14 into

the painting school, let alone the dress design department. There was a mass exodus every year into The

Royal College for a further three years of jollification. Peter Blake was

teaching there, we're good mates. The

kind of work a few of us were into related to being able to enjoy things that

were popular rather than going down the bleeding library all the time.”

Hey, Hey Mobile

Ian: “I met Betty,

my late first wife, at the Royal College of Art. She was at Newport College of

Art. Her dad went to the Royal College of Art in the thirties. Getting into the

RCA was the only thing I've aspired to in my life. I spent two years trying to

get in. It’s the only achievement I've ever felt, a bit like going to the

university of your choice. I’m really pleased I went there, I’m proud of it. I

wouldn't have been able to learn about how to live as a person doing what they

want to do if I hadn't gone there, allowing your determination and output to

control the way things go - my nine and my five.”

At the time of writing, a Kickstarter campaign has been launched to raise the £10,000 needed to ensure that the show goes ahead. Supporters have been asked to donate here:

http://www.kickstarter.com/projects/1996276438/ian-dury-more-than-fair-art-exhibition/

See you there!

Follow Will Birch on Twitter

Will Birch website

At the time of writing, a Kickstarter campaign has been launched to raise the £10,000 needed to ensure that the show goes ahead. Supporters have been asked to donate here:

http://www.kickstarter.com/projects/1996276438/ian-dury-more-than-fair-art-exhibition/

See you there!

Follow Will Birch on Twitter

Will Birch website